Signs of Financial Distress and Insolvency Risk in Latvia

Why early detection matters

Insolvency rarely arrives as a surprise to people who monitor cash and obligations weekly. For everyone else, it can feel sudden. Most insolvency cases are preceded by a period of tightening liquidity, delayed settlements, rising payables, pressure from lenders and suppliers, and increasingly reactive decisions. The earlier you identify the pattern, the more options you keep: renegotiate terms, cut losses, prioritise obligations, restructure debt, adjust pricing, and restore payment capacity.

This article is written for two practical scenarios: (1) assessing your own company and building an internal early‑warning system; (2) monitoring customers and suppliers to protect your cash flow. The approach is deliberately simple: combine a small set of official checks with a few financial and behavioural indicators, then trigger predefined actions.

Key concepts used in this guide

Liquidity vs solvency

Liquidity is the ability to meet near-term obligations using current assets (cash, receivables, inventory). Solvency is broader: whether the company can meet obligations sustainably over time and whether assets cover liabilities in a meaningful way. A business can be profitable but temporarily illiquid (e.g., slow receivables), or liquid for a short period but structurally insolvent (e.g., persistent losses and excessive leverage). Because of this, the best practice is to monitor both: short‑term cash buffer and long‑term capital structure.

Legal protection proceedings and insolvency (high level)

Latvian law provides legal protection proceedings (often referred to as restructuring under court supervision) that aim to restore a debtor’s capacity to settle obligations when the debtor is already in financial difficulty or expects to be. If restoration is not realistic, insolvency proceedings become the formal process with court involvement and strict stakeholder rules. For business decision‑making, the key takeaway is timing: earlier engagement usually creates more room for negotiated solutions.

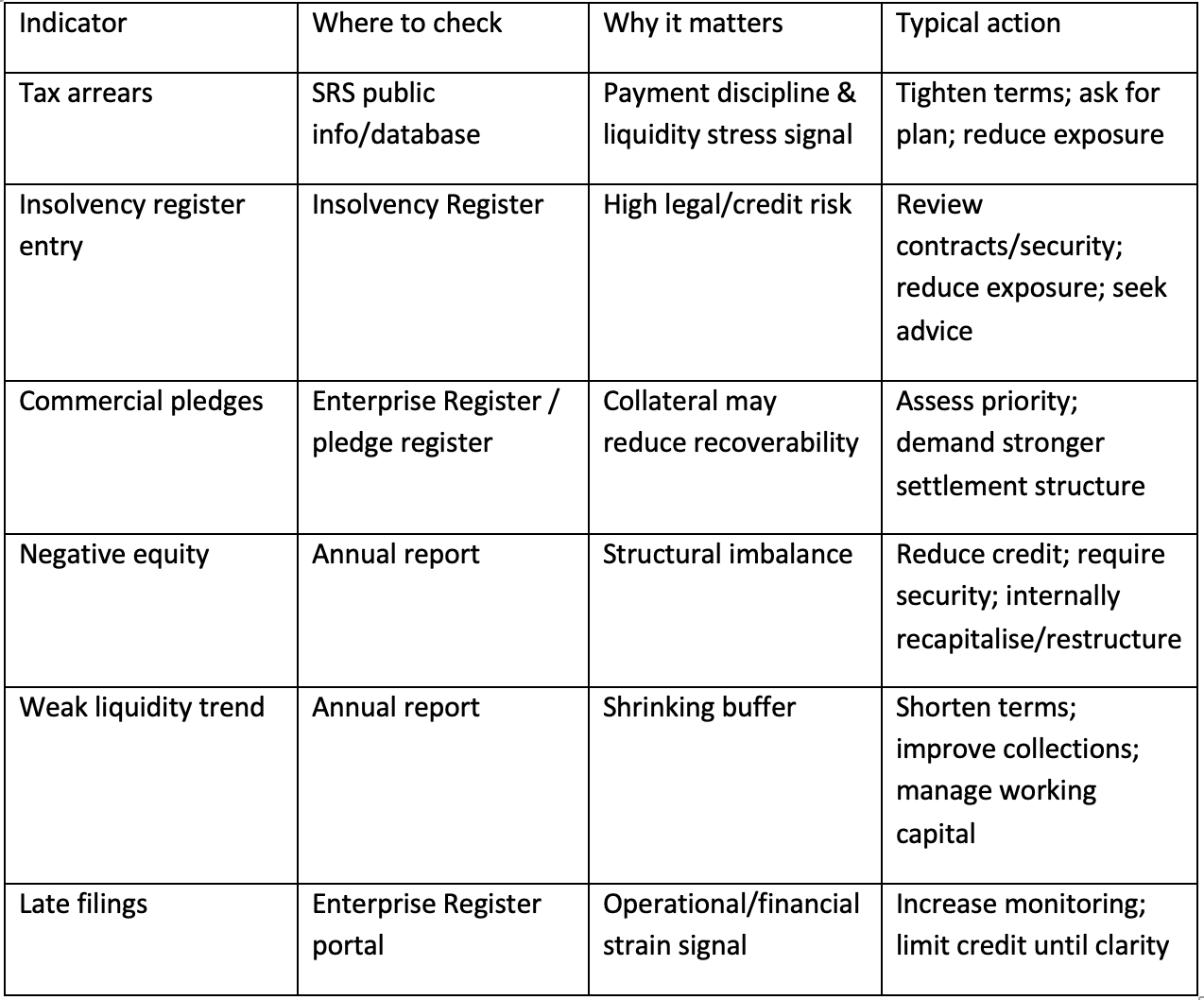

Quick official checks you can do in 10 minutes

Enterprise Register information portal (company profile, filings, pledges)

Start with official public data. Verify the company’s identity, management/representation rights, and whether filings are up to date. Check for commercial pledges (collateral), which can materially affect recoverability if the counterparty defaults. Also check annual report filing discipline: repeated late filings often correlate with operational strain.

Insolvency Register (ongoing proceedings and status)

An entry in the Insolvency Register is one of the clearest public warning signs. Even if the business continues operating, the legal context can change quickly: claims, enforcement actions, and creditor behaviour may accelerate. If you have exposure, immediately reassess contract terms, delivery conditions, and security.

Tax arrears (public information)

Tax arrears do not automatically equal insolvency. They may reflect disputes, schedules, or short liquidity gaps. Still, persistent arrears often correlate with delayed payments elsewhere. For risk control, treat arrears as a trigger to tighten terms (e.g., partial prepayment) until clarity is restored.

Financial statement signals that often show up first

Revenue trend, margin pressure, and the ‘loss‑making volume’ trap

Revenue decline across multiple years is a signal, but the quality of revenue is even more important. A common pattern in distress is ‘loss‑making volume’: sales continue, but pricing, discounts, and cost structure mean each additional unit adds strain. Watch for declining gross margin, rising operating costs without proportional revenue, and weak contribution by major customers.

Negative equity (structural red flag)

Negative equity means liabilities exceed assets. It often results from sustained losses, inadequate capitalisation, or overly aggressive distributions. Operationally, negative equity reduces supplier confidence, makes financing more expensive, and limits the company’s ability to absorb shocks. In counterparties, it is frequently associated with pressure to stretch payables and ask for longer settlement periods.

Liquidity ratios (how much buffer exists?)

Current ratio (Current assets / Current liabilities) is a simple starting point. A persistently low ratio suggests a thin buffer. Quick ratio can be more realistic when inventory is slow-moving. As a practical method, avoid single-year judgement: compare at least two or three years and look for direction (improving vs deteriorating). Also compare with industry reality: service companies often carry less inventory; manufacturing may have higher working capital needs.

Receivables and payables: where cash gets stuck

Receivables growing faster than revenue often indicates collection issues or lenient payment terms. Payables rising fast can signal that the company is financing itself through suppliers. The most concerning pattern is simultaneous growth in receivables and payables with no improvement in cash balance-cash is being absorbed by working capital. If you manage a company, an immediate tool is receivables ageing with strict follow‑up and escalation. If you monitor a customer, it is a reason to reduce credit exposure.

Accounting hygiene and filing discipline

Late annual reports, inconsistent disclosures, or frequent changes in accounting providers are not proofs of distress, but they are useful signals. In credit risk practice, such indicators are weighted together with payment behaviour and public register data to form an actionable risk score.

Behavioural and operational warning signs

Financial distress becomes visible in operational behaviour earlier than in annual statements. If the following repeat, treat them as an escalating pattern:

- rolling payment promises (‘next week’) without concrete dates and amounts;

- requests to change settlement structure (partial payments, split deliveries, unusual offsets);

- sudden aggressive discounting or panic‑style sales campaigns;

- high staff turnover, especially in finance and operations;

- asset sales or ‘urgent investor’ messages without transparent plan;

- quality and delivery issues (cash stress often disrupts procurement and staffing).

What to do: a structured action plan

If you monitor a customer or supplier (external risk control)

The goal is to control exposure while keeping cooperation possible. The best actions are usually boring and consistent: limit credit, make settlement predictable, and secure what matters.

- Set a credit limit and enforce it (do not increase it under pressure without new information).

- Move to partial or full prepayment when delays become systematic.

- For large exposures, request additional security (e.g., pledge or guarantee) and document it properly.

- Shorten payment terms and align delivery milestones with payments (stage payments).

- Diversify exposure to avoid dependency on a single counterparty.

- When restructuring is requested, require a written plan with dates and amounts; treat non‑compliance as a trigger to escalate.

If it’s your company (internal stabilisation)

When you face distress internally, the fastest way to regain control is to improve cash visibility and prioritisation. A practical sequence is: (1) visibility; (2) stabilisation; (3) negotiation; (4) structural fixes.

- Visibility: build a 13-week rolling cash plan (weekly). Include VAT/payroll/taxes, debt service, supplier payments, and realistic collections.

- Stabilisation: stop non‑critical spending, renegotiate recurring costs, pause non‑essential projects, and protect payroll/taxes to avoid compounding risk.

- Negotiation: approach key creditors early with a realistic schedule, not a wish. Provide numbers and commitments you can deliver.

- Collections: implement receivables ageing, strict reminders, and a clear escalation path (phone call → written notice → settlement plan).

- Structural fixes: review pricing, product profitability, customer concentration, and cost base. Eliminate loss‑making activities unless they have a clear strategic reason.

- Documentation: keep decisions and assumptions recorded (cash plan, creditor list, management minutes).

Governance: what directors should document and why

Under Latvian company law, directors are expected to act with due care. In distress, this translates into a practical standard: detect risk early, evaluate alternatives, act timely, and document decisions. From a risk perspective, documentation is not bureaucracy-it is evidence of a disciplined process and it improves decision quality. Maintain a ‘distress file’: rolling cash plan, creditor list, receivables ageing, key contracts and obligations, and management decisions.

A simple scorecard you can implement immediately

You don’t need dozens of indicators. Choose a small set, track them consistently, and tie them to actions. Below is an example that works for both internal monitoring and counterparty risk control.

Conclusion

The best protection against an “unexpected” insolvency is regular monitoring: checking public registers, tracking financial ratio trends, and taking clear action at the first warning signs. If needed, engage a financial specialist to build a cash flow plan, assess the key indicators, and structure safer settlement/payment terms.

Sources:

- Insolvency Law (Latvia) – Likumi.lv

- Commercial Law – directors’ liability (Article 169) – Likumi.lv

- Accounting Law – management duties – Likumi.lv

- Annual Reports and Consolidated Annual Reports Law – Likumi.lv

- State Revenue Service: Tax debt information

- SRS public database: Tax debtors (NPAR)

- Enterprise Register information portal

- Enterprise Register: Insolvency Register (info)

- Insolvency Register search

- Enterprise Register: Commercial Pledge Register

- Commercial pledge e‑service

- Supreme Court: case law on directors’ liability

- Ministry of Economics: Legal protection proceedings (TAP)

- Bank of Latvia: Financial Stability publications

Last updated 2026, February 17